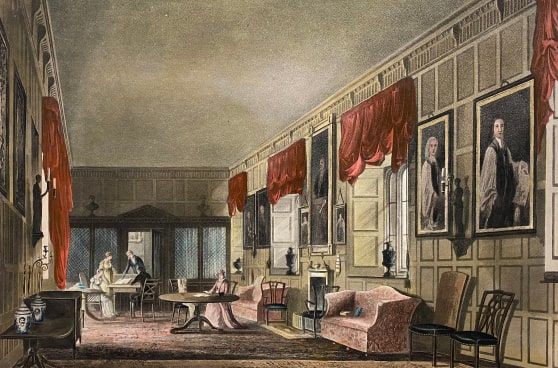

The Great Chamber was originally created in the 1540s as part of a palatial mansion built from the ruins of the Carthusian monastery. It was further embellished by the Duke of Norfolk in around 1570, when a grand fireplace and a lavishly decorated ceiling were installed. The Great Chamber was designed as a grand formal room of splendour and prestige. It was where Elizabeth I met her Privy Council in 1558 in the days before her coronation, and James I created 130 Knights. After 1611, when the site became an almshouse and a school, it was used for the governors meetings.

The room was rebuilt in the 1950s following fire damage during the second world war, and was refurbished again in 2020 as part of a National Lottery Heritage Fund project. This latest project was intended to recapture the historic grandeur of the room rather than reconstructing its design specific to any one historical period.