In a bid to help define the lush Norfolk Garden Justin Dennis, Head of Horticulture at the Charterhouse, contacted me to help with a design challenge.

Set against the backdrop of a Tudor brick wall, onto which the Duke of Norfolk vaingloriously set an oversized ANNO 1571 when adapting the former cloister into a Garden Gallery, the Norfolk Garden is one of the Charterhouse courtyard gardens’ softer spaces. It is situated between the north façade of the Tudor mansion, the Victorian Queen Elizabeth II building, and the 14th century cloister. Its secluded spaces blow and drift with lush dark greens, pink roses and purple clematis in summer, and red camellias in winter. It’s perfect for weddings, summer parties and the sort of occasion from which you want a photo as a memento.

We saw an opportunity to strengthen this garden room in pursuit of just such a sense of conviviality. The box-edged herb garden marking its narrow front edge had to go, given the inevitability of box blight. A room likes a door, but all we had was a lintel – a York stone path cuts this herb garden in two directing the passer-by into the Norfolk Garden’s two levels of lawn. The Victorian arcade to its north had once extended southward to cover this space. It had later been removed by architects Seely & Paget during their extensive post Second World War restoration work.

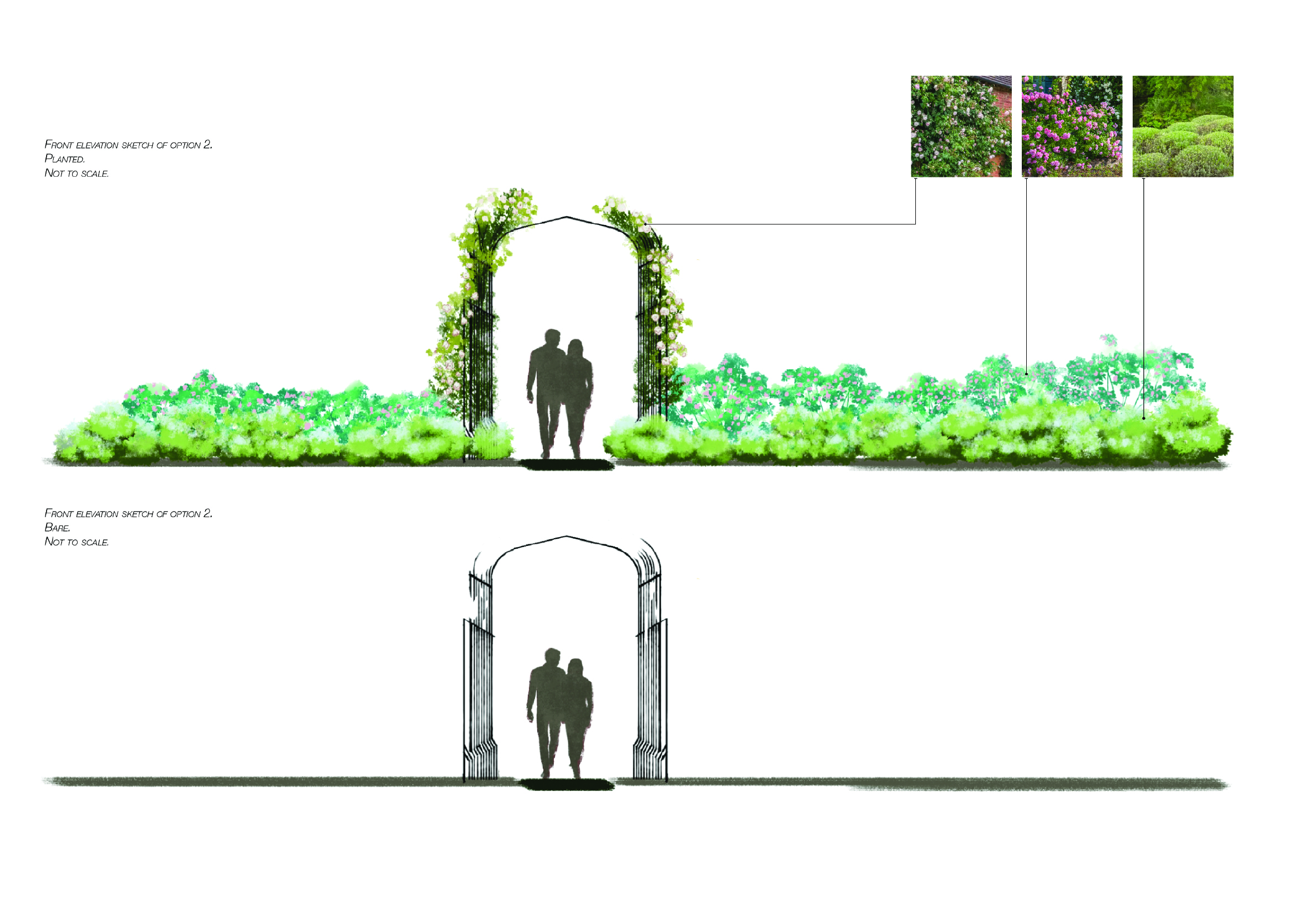

Our initial discussions kept landing on a weaving-together of eras coalesced into a portal over this path, in the form of a Tudor arch to reference the arcade. The Tudor mansion at the Charterhouse’s heart refers back to the Carthusian monastery it had been. The Victorian arcade refers back to the four-centred form of the Tudor arch typology, and subsequently part of the arcade had been destroyed. I referred back to this destruction with the arch’s fractured form. Referring forward via digital technologies, I captured the form of the remaining arches with a LiDAR scan, taking the new arch’s geometry directly from this. Initial sketches also reference Instagram, incorporating diagonal structural elements that direct sightlines to a group standing beneath the arch as if staged for a memory to be captured in a photograph, or social media post.

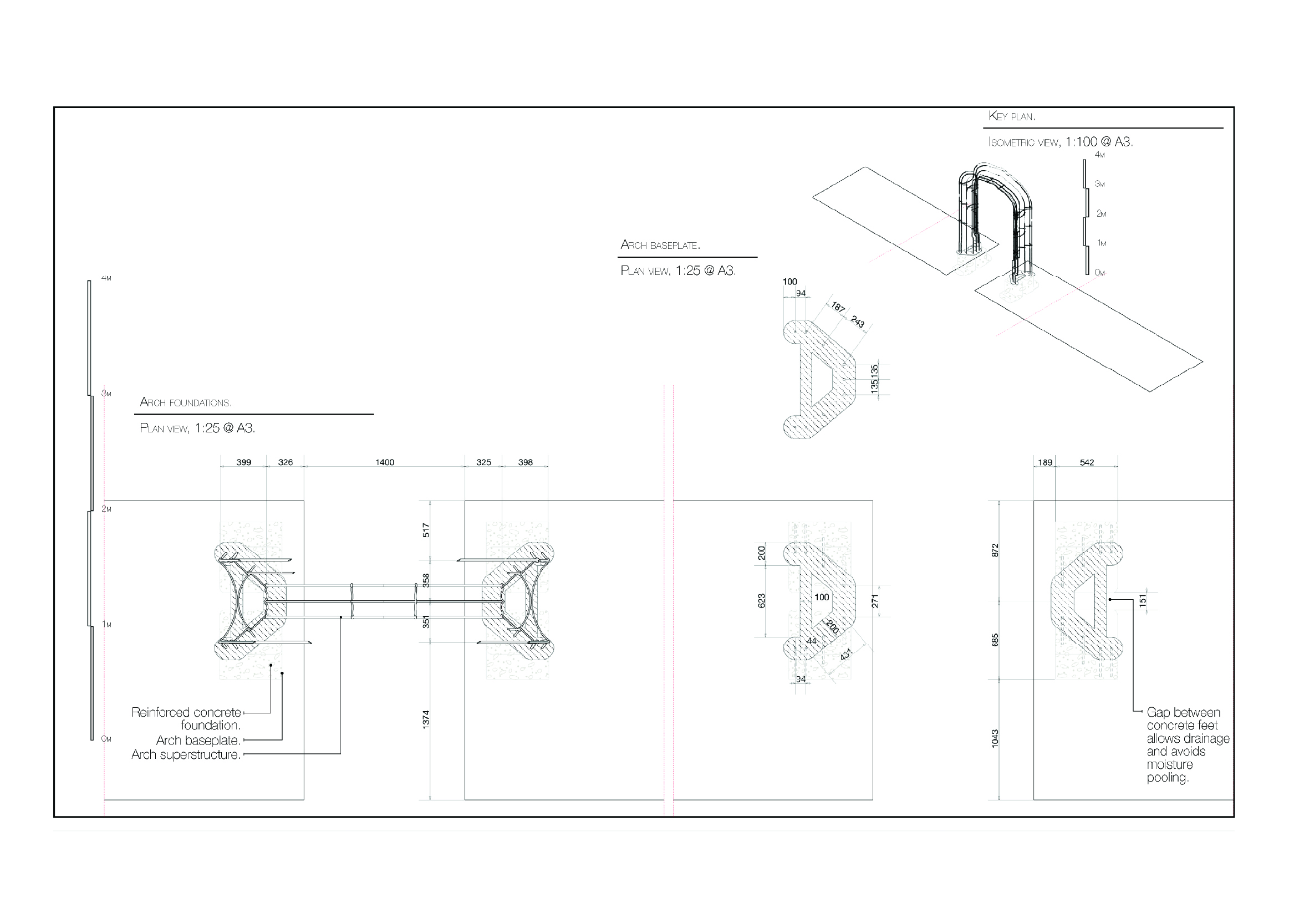

Hovering between sculpture and landscape architecture, the new arch existed for a time only in digital form. Polycam scanned the existing form for a precise geometry, producing a point cloud. This was imported into Rhino, and its vertices extracted and formed into digital verticals. Conceptually it was resolved into a ghostly fragment of earlier layers of inhabitation. In an essay I look to often, the sociologist and writer of places Tim Ingold clarifies that a palimpsest – a sheet of vellum overwritten many times – is re-inscribed only after the writing hand has scraped prior writings clean with a knife. This is contrary to what many cite as its usual quality which is covering. The absorbent lambskin retains traces of its prior inkings, and each bout of abrasion uncovers them further. The newest marks are clearest, but many rounds of records show through. The landscape, the surface of the ground, functions similarly in a place such as the Charterhouse. Ingold goes further to point out the poignant etymology of our word for a leaf in a written story, a page, or a pagus, a planted Roman field.

“The past comes up as the present goes down. This is not a layering so much as a turning over.”[1] A palimpsest, a medieval text of scholarship illegible to most in that era and sequestered behind walls, forms an apt point of reference for an intervention into the landscape of the Charterhouse today. Other references were considered as digital design progressed with input from the ironmonger Oliver Russell from The Forge in Headley, Hampshire. The crossbars necessary for the arch’s stability were resolved into an arrangement something like the notation for a Pérotin polyphony, such as other monks- not the silent Carthusians- would have sung in the fourteenth century. Excavating and pouring the foundations in November in time for them to cure, we uncovered shards of blue and white tableware, and fragments of several clay pipes which Bethany from the Visitor Engagement Team told us would have been smoked in the 17th century.

In January the Charterhouse gardeners and I visited The Forge to see the structure for the first time. When working with digital models, anything can change and physics doesn’t apply. Oliver helped us to understand the physical object and allowed us to have a go at the anvil; heating, beating and drawing out the steel members as he would continue to do until he’d formed all the pieces. Late in March he drove it up to the Charterhouse on the back of a lorry and, with his team, bolted the sides to the foundations, raised the top onto the sides, riveted them together and it was done.

Blanched in a bath of zinc to give it a blue-grey bloom, the new Norfolk Garden arch has a tendency to shift in perceived scale depending on the light and where you’re standing. When you’re standing under it, as I hope you’ll find the opportunity to do, it appears at least your height again above you. From any distance it falls in step with the arcade to its north, the Duke of Norfolk’s wall behind or, should you visit after the summer when the leaves have fallen, the supine ‘skeletons’ of the mulberry trees at either side of Preacher’s Court. With one of the Barbican towers and the Charterhouse Chapel’s cupola framed through it, the past and present play tag on the vertical axis.

Gardens get better with age. Now we only need to wait for the pale pink ‘New Dawn’ roses planted at the arch’s sides to climb its height and evening parties to linger underneath, gracing it with the presence of nearby conversations, between bees and between guests, to enliven this expression of the traces left by centuries of others.

Ryan Carter is a landscape architect, writer, and Special Projects Director at Martha Schwartz Partners. Holding an MLA from the Bartlett School of Architecture, from 2012 to 2021 he founded and directed The Seasons Bureau, a landscape architecture consultancy in Shanghai. He can be reached at ryan@seasonsbureau.com. All photos (c) Ryan Carter.

[1] Tim Ingold, “The Earth, the Sky and the Ground Between,” Metode (2023), vol. 1 ‘Deep Surface’